In several recent posts here at Practical Theology Today, we have lingered over a phrase that stood at the heart of Jesus’ proclamation: “the kingdom of God has come near.” We explored what it meant for God’s reign to draw near – how the kingdom was not merely a distant heaven waiting for us someday, but God’s active rule breaking into the ordinary world.

That announcement formed the center of Jesus’ message. But it was not the only thing He said. Mark preserved Jesus’ earliest summary of His preaching in a remarkably compact form:

Now, after John was taken into custody, Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of God, and saying, “The time has come, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent and believe in the gospel.” (Mark 1:14–15)

In two short verses, Mark gave us the core vocabulary of Jesus’ ministry: kingdom, repent, believe, and gospel.

These words are familiar to most Christians. Perhaps too familiar. Over time, they have accumulated layers of assumption, tradition, and misunderstanding. We often hear them through modern religious filters rather than through the world in which Jesus first spoke them.

In the posts ahead, we will slow down a bit and take a closer look at the words Jesus used when announcing the kingdom. So, we begin a short series called…

Not What You Think It Means.

The Beginning of the Good News

Before Mark recorded Jesus’ proclamation in Galilee, two important events had already unfolded.

First, John the Baptist had appeared in the wilderness, calling Israel to repentance and preparing the way for the coming One (Mark 1:1–8). John’s ministry created a sense of anticipation. Something was about to happen. God was stirring again among His people.

Then Jesus came to the Jordan and was baptized. As He came up out of the water, the heavens were torn open, the Spirit descended upon Him, and the Father’s voice declared, “You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased” (Mark 1:11).

Immediately afterward, the Spirit drove Jesus into the wilderness, where He faced temptation for forty days (Mark 1:12–13). There, in solitude and testing, Jesus confronted the rival voices that would attempt to define His mission.

Only after these events did Jesus step into public ministry.

And Mark noted one more detail: John had been arrested. The prophetic voice that prepared the way had been silenced by political power. Yet the message did not stop. Jesus began proclaiming the same kingdom John had announced – but now with a new authority.

The Words that Framed the Message

Mark summarized Jesus’ preaching in a single sentence:

“The time has come… the kingdom of God has come near; repent and believe in the gospel.”

Every word in that sentence mattered.

Jesus was announcing that history had reached a decisive moment – “the time has come.” The long story of Israel’s hope was reaching its fulfillment.

And the reason was clear: the kingdom of God had come near.

In previous posts, we explored what that meant. The kingdom was not simply a future destination. It was the reality of God’s reign drawing near, in and through Jesus Himself. Wherever Jesus went, the rule of God came close enough to be encountered.

But notice what followed the announcement. Jesus did not simply declare the kingdom’s nearness. He invited a response:

- Repent.

- Believe.

- Receive the gospel.

Those three words – repent, believe, gospel – have shaped Christian vocabulary for centuries. Yet the meanings we often attach to them are not always the meanings Jesus intended. Which raises an important question:

What did Jesus actually mean when He said, “Repent and believe in the gospel”?

Luke’s Window into Jesus’ Mission

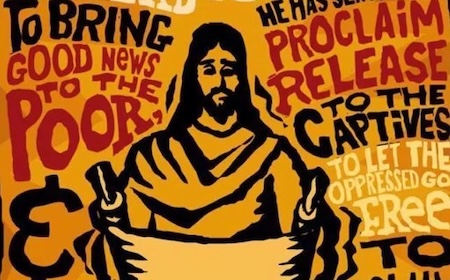

As you may recall, Luke recorded what many consider to have been Jesus’ mission statement – The Spirit of the Lord is upon me… (Luke 4:16-20). Jesus described the kind of kingdom He was bringing: one that liberated, restored, healed, and welcomed the marginalized.

Mark’s summary in 1:14–15 functioned differently. Instead of describing the mission, it captured the core announcement and invitation that accompanied it. Put the two together, and we begin to see the shape of Jesus’ message:

- Luke 4 showed us what the kingdom looked like when it arrived

- Mark 1 showed us how people were invited to respond when they heard about it

Both passages pointed to the same reality: God’s reign had drawn near in Jesus.

Words We Think We Know

Here’s where our problem begins. When modern readers hear the words repent, believe, and gospel, we often import meanings that developed much later in Christian history.

For example:

- Repent is frequently heard as feeling sorry for personal sins.

- Believe is often reduced to mentally agreeing with certain doctrines.

- Gospel is sometimes understood as a formula for how individuals go to heaven when they die.

But when Jesus first spoke those words in Galilee, His listeners heard them within the larger story of Israel and the announcement that God’s kingdom was arriving.

Those words carried layers of meaning connected to that announcement. They were not isolated religious commands; they were responses to the nearness of God’s reign.

To hear them rightly, we need to step back into that moment in Mark’s Gospel – when Jesus walked into Galilee and declared that something new had begun.

Where This Series Is Going

In the coming posts in this series, we will slow down and revisit these familiar words one by one.

- What did Jesus mean when He said, “repent”?

- What did it mean to “believe” in the context of the kingdom?

- And what exactly was the “gospel” Jesus proclaimed?

Each of these words has often been simplified, reduced, or misunderstood in modern Christian vocabulary. Yet when we recover their original context, their meaning begins to come to life.

And when they do, something remarkable happens. We start to hear Jesus’ invitation the way His first listeners did – not merely as religious terminology, but as a call to reorient our lives around the nearness of God’s kingdom.

So this short series will explore some of the most familiar words in the Christian faith.

Words we think we know.

Words that may not mean quite what we think they mean.

And words that, once rediscovered, may help us hear the message of Jesus with new ears.