The people of God knew what it meant to lose everything. Jerusalem was in ruins, the temple was ashes, and the people had been carted off to Babylon in humiliation. Decades passed. A generation grew up in exile,* remembering only in stories the songs of Zion and the glory of Solomon’s temple. When the exile finally lifted and the return began, their task was clear but overwhelming: rebuild. Rebuild their homes, rebuild their city, rebuild their temple, rebuild their life with God.

It is in this season that we meet Ezra and Nehemiah – two leaders who carried the weight of restoration on their shoulders, but in different ways. Ezra, the priest and scribe, devoted himself to restoring worship and the teaching of God’s Word. Nehemiah, the cupbearer turned governor, devoted himself to rebuilding the city’s walls and restoring its strength. Both men lived in the tension of hope and hazard. Both knew that what they built was far more than stone and timber; it was a testimony that God had not abandoned His people.

Ezra and the Temple: Restoring Worship

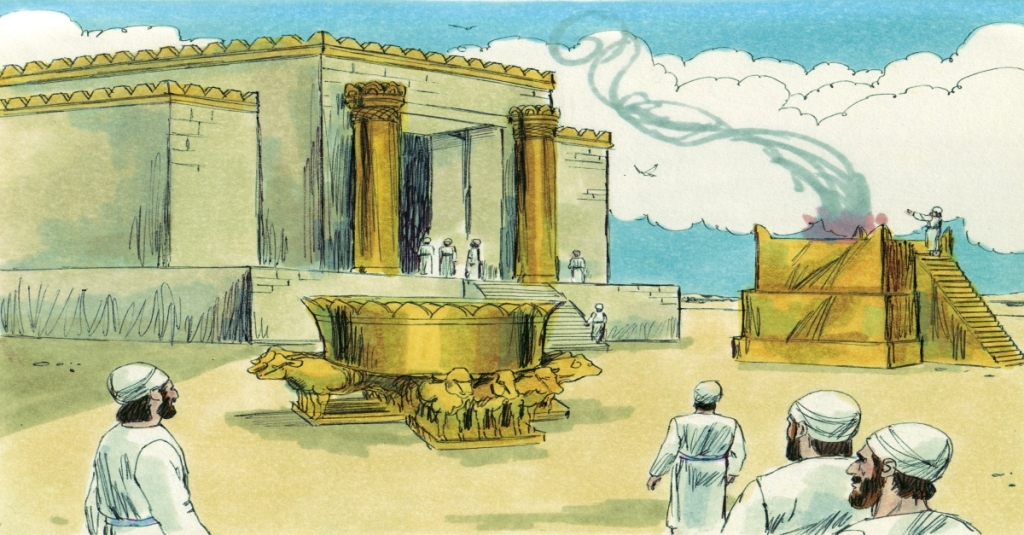

The first wave of exiles returned under Zerubbabel, rebuilding the altar and eventually completing the Second Temple around 516 BC. It was nothing like Solomon’s grand temple, but it was a place where sacrifices could be offered and the presence of God honored. When Ezra arrived some decades later, the Second Temple already stood, but worship had become compromised. People had intermarried with surrounding nations, idolatry lingered at the edges, and the Word of God had been neglected.

Ezra’s mission was not just about stone and mortar – it was about hearts. Scripture describes him as a man who “set his heart to study the Law of the LORD, and to do it and to teach his statutes and rules in Israel” (Ezra 7:10). He called the people back to covenant faithfulness, sometimes with tears, sometimes with stern confrontation. His leadership shows us that rebuilding life with God is not only about physical structures but about returning to obedience and worship.

Ezra faced resistance, of course. Neighboring peoples mocked the efforts of the returned exiles, writing letters to Persian kings to halt the work. Within Israel, there was compromise and half-heartedness. Some resisted his calls to repentance. Yet, slowly, through public reading of the Law and renewed devotion, Ezra helped re-center the people on God.

Nehemiah and the Walls: Restoring Strength

If Ezra carried the priest’s burden, Nehemiah carried the builder’s grit. Serving as cupbearer to King Artaxerxes, he heard word that Jerusalem’s walls lay in ruins and its gates burned. His response? He wept. He fasted. He prayed. And then he risked everything by asking the king for permission to return and rebuild.

When he arrived, he found a city vulnerable and exposed. A city without walls was a city without security, dignity, or identity. Nehemiah walked the ruins at night, surveying the broken stones, and then rallied the people: “You see the trouble we are in… Come, let us rebuild the wall of Jerusalem, and we will no longer be in disgrace” (Neh. 2:17).

But the work was not easy. Opposition sprang up quickly. Leaders like Sanballat and Tobiah ridiculed the project: “What are these feeble Jews doing? … If even a fox climbs up on it, he will break down their wall of stones!” (Neh. 4:2–3). Their mockery turned to threats, and the builders worked with one hand on the stone and the other on their swords. Hazards came from without and within: enemies plotted attacks, while discouragement and fatigue weighed heavily on the workers.

Nehemiah demonstrated true leadership in those moments. He stationed guards, encouraged the weary, and reminded them that the work was God’s. He called out corruption, confronted injustice among the nobles, and kept his own life free of greed. Through sheer perseverance and faith, the wall was completed in just 52 days – a feat that even their enemies had to admit was possible only because “this work had been accomplished with the help of our God” (Neh. 6:16).

The Attitudes of the People

Ezra and Nehemiah both encountered a spectrum of reactions. Some rejoiced at the rebuilding. When the temple’s foundation was first laid, younger voices shouted for joy while older ones wept, remembering the glory of Solomon’s temple (Ezra 3:12). There was excitement and sorrow mingled together—the joy of restoration and the ache of what had been lost.

Others resisted, either through apathy or hostility. Some within the community were more concerned about their own houses than God’s house. Others opposed the reforms that called for sacrifice or repentance. And of course, enemies outside of Israel actively tried to sabotage the work.

Yet through it all, the people gathered. They took their places on the wall. They listened to Ezra read the Law for hours on end, standing in the hot sun. They confessed their sins together. They signed a covenant renewal. The story of Ezra and Nehemiah is not simply about two leaders but about a community that, with all its imperfections, rose to the occasion and chose to hope in God’s promises.

God’s Faithful Restoration

The stories of Ezra and Nehemiah are about more than ancient history. They remind us that God is in the business of restoration – He always has been, He always will be until the “renewal of all things” (Matt. 19:28). His people may stumble, cities may fall, worship may grow cold – but He stirs leaders, awakens communities, and rebuilds what was broken.

Ezra reminds us that restoration begins with returning to God’s Word and realigning our lives with His will. Nehemiah reminds us that God calls us to action, to pick up stones, to stand watch, and to persevere in the face of opposition. Together, they paint a picture of faith that is both spiritual and practical, both inward and outward.

And perhaps the most important lesson? The temple and the walls, as important as they were, pointed to something greater. Generations later, Jesus would walk those same streets, declaring Himself the true temple (John 2:19) and the Good Shepherd who protects His people.

The story ends where ours begins: with a God who restores, a people who return, and a future secured not by stone walls or earthly temples, but by the presence of Christ, through the Holy Spirit, among us.

* Exile: think “eviction.” In I Almost Bought the Farm, we discussed that the land, the Promised Land, belonged to God, and His people resided there at His pleasure.