Frank Tillapaugh once told a story that has never quite let go of me.

In Unleashing the Church, he described a church struggling to figure out how to minister to trailer-court kids in their neighborhood. As committees met to discuss various programming options, a group of Young Life leaders quietly started ministering to the kids. Rather than running programs for kids who lived in the trailer court, they chose to move into the neighborhood. They showed up at sandlots and basketball hoops, laundromats and front porches. Over time, relationships formed – not because of program strategy, but because of proximity. Presence did what programming never could.

Tillapaugh’s point was simple and unsettling: transformation often begins not with proclamation, but with incarnation.

John, in the opening of his Gospel, made a strikingly similar claim…

“And the Word became flesh and lived among us…” (John 1:14)

While many English translations render the phrase as “lived among us,” John’s language carried far greater weight. The Word did not keep a divine distance. The Word tabernacled among us.

God moved into the neighborhood.

The Word Who Pitched a Tent

The Greek verb John used – eskēnōsen – literally meant “to pitch a tent” or “to dwell in a tabernacle.” John was not being poetic for effect; he was making a strong theological claim.

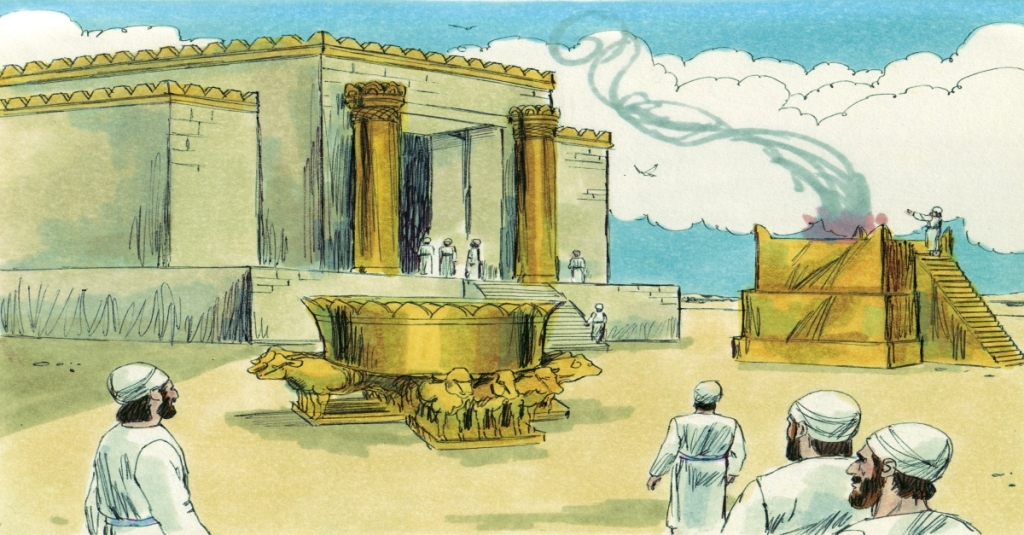

For Israel, the tabernacle was the first place God’s glory took up residence among the people. It was portable, humble, and situated right in the middle of the camp. God was not distant. God traveled with them – through wilderness, uncertainty, and vulnerability.

Later came the first temple built under Solomon: permanent, majestic, and symbolically central. God’s presence was no longer housed in fabric and poles, but in stone and cedar. The second temple, rebuilt after exile, carried the same hope with far more ache – glory remembered, longed for, but never quite restored.

Across the tabernacle and temples, one theme held steady: God desired to dwell with His people. Yet access remained limited. Curtains, courts, sacrifices, and priests all served as reminders that something still stood between heaven and earth.

John was telling his readers that the long story had turned a corner. The dwelling place of God was no longer a structure. It was a person.

Glory With Skin On

John continued: “We have seen his glory.”

That word – glory – would have triggered memories of cloud and fire, of Sinai and the Holy of Holies. Glory was weighty, dangerous, and awe-inducing. It surpassed superficiality.

And yet here, glory wore skin.

It ate meals. It attended weddings. It touched lepers. It wept at gravesides. The glory that once filled sacred space now filled ordinary places. God’s presence was no longer something one traveled toward, but something that drew near.

Eugene Peterson famously paraphrased John 1:14 this way: “The Word became flesh and blood, and moved into the neighborhood.”

That is not a sentimental phrase. It is a kingdom announcement.

The Kingdom at Hand

When Jesus stepped into Galilee proclaiming, “The kingdom of God has come near,” he was not introducing a new idea. He was naming what had already become true.

The kingdom was “at hand” because the King was standing there.

Before Jesus preached a sermon, healed a disease, or forgave a sin, the kingdom had already arrived in embodied form. God’s reign showed up not first as instruction, but as presence.

This reframed everything!

The kingdom of God was no longer confined to sacred space or guarded by religious systems. It was now encountered wherever Jesus went. Fields became holy ground. Dinner tables became sanctuaries. Roadside conversations became moments of revelation.

Incarnation Before Instruction

This is where John 1:14 quietly challenges many of our instincts about ministry, discipleship, and witness.

We often want to start with explanation – beliefs clarified, doctrines defended, behaviors corrected. Jesus began elsewhere. He began by dwelling. By staying. By being present long enough for trust to grow.

Like those Young Life leaders in the trailer court, Jesus did not love from a distance. He crossed boundaries of comfort and respectability. He entered neighborhoods others avoided. He made himself interruptible.

The incarnation was not only theological in nature; it was fundamentally missional.

God did not shout salvation from heaven. God walked it into town.

A Dwelling That Still Continues

John’s language also carried a quiet promise forward. If God once dwelled in a tent, then a temple, and now in Jesus, where does God dwell now?

The rest of the New Testament dared to answer: among a people shaped by the same Spirit who anointed Jesus. The presence that once filled sacred space now fills human lives.

Which means the question is no longer whether God desires to dwell among us. The question is whether we are willing to dwell among others in the same way.

The kingdom comes close again and again wherever followers of Jesus resist power and prestige in favor of presence and proximity.

God moved into the neighborhood. He invites us to do the same.