A continuation of my experience chasing after high school track and cross country kids….

Circa mid-1980s. I was in my mid-30s, volunteering with the track team at a high school where I was also a Young Life leader. A couple times a week I was available to run with the team. I showed up for the first spring practice anticipating running with guys I already knew. There was a plethora of freshmen distance runners that year and the coach asked if I would take them out for a run. Since there was still snow on the track, the workout was road running.

When we got out on the road they all took off like jackrabbits, leaving me to chase after them at a pace faster than my normal (I think they thought I was a coach and wanted to impress me). About halfway through the run, I had chased down half of the group, much to their surprise. What I knew that they didn’t know was that the workout finished up a steep hill where I caught the rest of the group and passed them. Justice!

In the last blog post, we looked at the Apostle Paul’s admonition to Timothy to run away from the things that tend to entrap Christ-followers and…

Instead, chase after justice, godliness, faith, love, patience and gentleness (1 Timothy 6:11, NTFE)

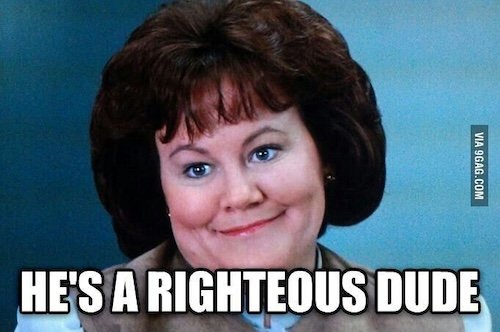

What does it mean to chase after justice? Instead of justice, most translations use a religious term we are quite familiar with but probably unable to describe or define – righteousness. It is one of those biblical terms we often read without thinking about its meaning. What is righteousness? And how is it related to justice?

The Greek word Paul used for righteousness is dikaiosynē. According to Bill Mounce it occurs 92 times in the New Testament, 10 times attributed to something Jesus said (e.g. the well-known Matthew 6:33 passage: Seek first his kingdom and his righteousness [dikaiosynē]…). This is not going to be an exhaustive study of dikaiosynē – books have been written on this one word alone. But I do want to provide us (me included) a better understanding of the elusive term righteousness and get a glimpse as to why it can be translated as justice.

Mounce’s basic explanation of dikaiosynē using English words: righteousness, what is right, justice, the act of doing what is in agreement with God’s standards, the state of being in proper relationship with God. As typical, it takes a lot of English words to capture the essence of a single Greek word.

In Greek philosophy and ethics (think Aristotle and Plato), dikaiosynē is closely related to the idea of moral virtue and the proper conduct of individuals within a society. Dikaiosynē is often associated with the idea of treating others fairly, acting justly, and upholding moral integrity. In a broader sense, it encompasses the concept of moral rightness and adherence to ethical principles.

Since righteous is one of those biblical terms we often read without thinking about its meaning, I suspect we tend to default to Merriam-Webster’s definition that points to a connection with morality which in our minds translates into “right living,” something we must do or work at. Our individualistic Western faith can easily hear it this way – it’s about me living the right life. But it appears that dikaiosynē is much more than that.

When the OT was translated from Hebrew to Greek (the Septuagint), the translators used dikaiosynē to describe both righteousness and justice. Psalm 33:5 is a good example:

- Hebrew: “He loves righteousness (tsedeq) and justice (mishpat); the earth is full of the steadfast love of the LORD.”

- Greek (Septuagint): “He loves mercy and justice (dikaiosynē); the earth is full of the mercy of the Lord.”

The well-known passage, What does the Lord require of you? To act justly [mishpat] and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8, NIV), the Septuagint translates as to practice justice [dikaiosynē], and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God. We can see that dikaiosynē is not limited to individual righteousness but extends to the idea of social justice. All scripture calls for believers to act justly, show mercy, and advocate for the well-being of others, reflecting God’s righteous character in their interactions with the world.

It’s something worth chasing after.

Dikaiosynē is frequently used to describe the righteousness of God. It emphasizes God’s moral perfection, justice, and faithfulness to His covenant promises. The root Hebrew word for righteous/righteousness is tsedeq which speaks of God’s loyalty and reliability and his covenant (commitment) to humanity. Psalm 50:6 is a good example: And the heavens proclaim his righteousness [Hebrew: tsedeq; Greek: dikaiosynē,] for he is a God of justice.

For humans, tsedeq is a term of relationship describing a desire to live a life pleasing to a righteous God and a desire to live a life fitting to the members of God’s family. Simply stated, God is the righteous one and human righteousness is therefore a desire, a willingness to behave toward God and his people with the same care, compassion, and integrity that the righteous God has shown us.

It’s something worth chasing after.

Martin Luther, commenting on Galatians 2:20, wrote: Paul explains what constitutes true Christian righteousness. True Christian righteousness is the righteousness of Christ who lives in us. We must look away from our own person. Christ and my conscience must become one, so that I can see nothing else but Christ crucified and raised from the dead for me. If I keep on looking at myself I am gone. If we lose sight of Christ and begin to consider our past we simply go to pieces. We must turn our eyes to… Christ crucified, and believe with all our heart that he is our righteousness and our life. For Christ, on whom our eyes are fixed, in whom we live, who lives in us, is Lord over the law, sin, death, and all evil.

Chasing after righteousness isn’t about just living rightly, but chasing after the One who will transform us, becoming like him. As we become more like Him we will live more rightly which naturally includes living justly.

It’s certainly something worth chasing after.

.