When we think of the Temple in Jerusalem, it’s easy to imagine it as just another impressive ancient building with ornate stonework, golden decorations, and sacred rituals. Most cultures in the ancient Near East had temples. From Egypt to Mesopotamia, from Canaanite shrines to Babylonian ziggurats, temples were everywhere. They were designed to house the presence of the gods, to be places where heaven and earth touched.

Israel’s Temple was different.

From Tabernacle to Temple

The Temple wasn’t Israel’s first “house of God.” In the wilderness, God instructed Moses to build the tabernacle (Exodus 25–31). This portable sanctuary, crafted with careful instructions and exact measurements, was the meeting place between God and His people. Its very design taught theology: the Holy of Holies symbolized God’s throne room, the ark His footstool, and the altar His provision for forgiveness.

And behind it all was the Biblical covenant refrain: “I will take you as my own people, and I will be your God” (Exodus 6:7). The tabernacle was God’s visible way of saying, “I’m not a distant deity. I dwell with you, because you are mine.”

When Israel settled in the land, King David longed for a permanent place where God’s presence would rest. As he looked out from his cedar palace in Jerusalem, he was struck that the ark of the covenant still dwelled in a tent (2 Samuel 7:1-2). His desire was honorable – he wanted to build a house worthy of Yahweh.

But God said no.

Why David Was Not the Builder

God’s response to David was layered. First, He reminded David that He had never asked for a house – He was the One who had always been on the move with His people. Second, God turned David’s request upside down: instead of David building God a house, God promised to build David a “house” – a dynasty through which His kingdom would be established forever (2 Samuel 7).

Upside down. Another Biblical theme.

Another reason, Scripture notes, is that David was a man of war, his hands stained with blood (1 Chronicles 28:3). If they were to have a temple, God wanted it to be built by a man of peace – Solomon. But even more, God wanted to remind Israel: “I am the One who builds. I am the One who establishes.“

Temples Then and Temples Now

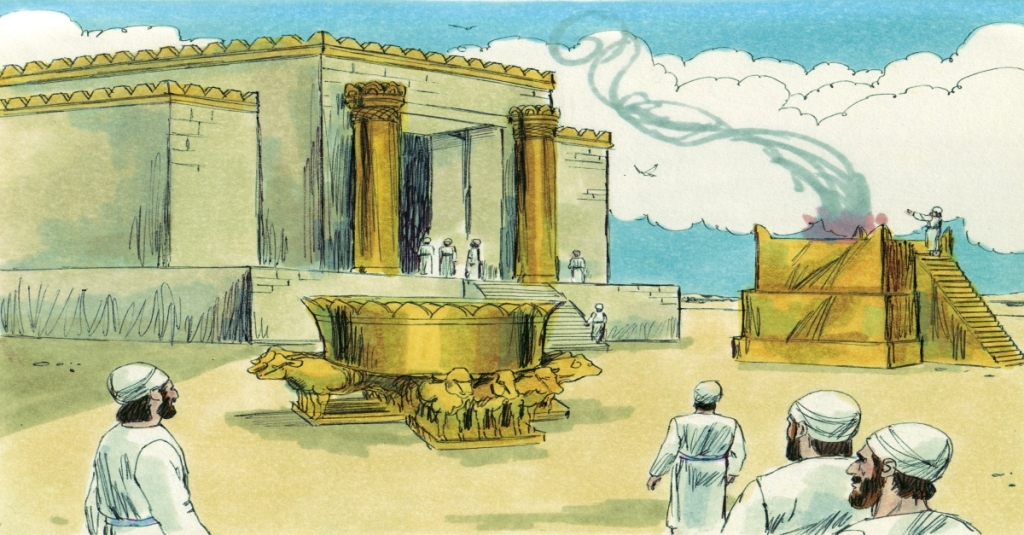

On the surface, Solomon’s Temple resembled other temples of its time: a sacred inner chamber, priestly rituals, sacrifices, and an emphasis on order and beauty.

But the distinction was profound. Pagan temples were built to contain an image of the pagan god with a carved idol that embodied the deity’s “presence.” In contrast, Israel’s Temple was built for the presence of the living God Himself. No idol sat in the Holy of Holies – only the ark of the covenant, a symbol of God’s throne. And when Solomon dedicated the Temple, God’s glory, in a theophany, filled the house like a cloud (1 Kings 8:10–11). Yahweh Himself took up residence.

Temple Theology 101

The Temple stood as more than an architectural marvel. It declared foundational truths about God and His kingdom:

- God dwells with His people. The Temple embodied the covenant promise: “I will be your God, and you will be My people.”

- God is holy. Access to His presence was carefully ordered, with layers of increasing sanctity leading to the Holy of Holies.

- God provides atonement. Sacrifices reminded Israel that sin separates humanity from God, and blood was necessary for forgiveness.

- God reigns as King. The Temple was His throne room in Jerusalem, reminding Israel they were His covenant people under His rule.

The Temple wasn’t just a religious building – it was a kingdom declaration.

The Greater Temple: Jesus Christ

Yet the Temple was never the ultimate goal. It was a shadow pointing forward to something greater. When Jesus arrived, He referred to Himself as the true Temple: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (John 2:19). In Him, God’s presence didn’t merely dwell in stone walls, but it walked among us in flesh and blood. The Word became flesh and tabernacled among us (John 1:1`4, AMPC).

Paul captures this beautifully in Colossians 1:15: “The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation.” Unlike the pagan temples with their carved images, Jesus Himself is the true image of God. He is not a symbol but the reality – God’s presence embodied fully.

And through Him, the covenant refrain takes on its deepest meaning: because of Jesus, God can say to Jew and Gentile alike, “I will be your God, and you will be My people” (2 Corinthians 6:16).

Dwelling with God Forever

From tabernacle to Temple to Christ, the story is one of God’s presence with His people. What began as a tent in the wilderness finds its completion not in stone, but in a Person – and ultimately, in a city where God Himself will dwell with humanity forever: “God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God.” (Revelation 21:3).

The Temple reminds us that God’s desire has always been to take up residence with His people. And in Jesus, that desire has been fulfilled in ways far greater than David or Solomon ever imagined.